She's a Model...

Fig. 1, Maquette of an idea that may become my end of year project proposal

Above (fig. 1) is a photograph from the inside of a not to scale model of the lecture room in the Calcutta Annex. Roll back a few weeks to the beginning of the year, I was starting to think about what my Major Project would look like. Around this same time I found myself questioning what making is. The questioning of making introduces the notion of worth and value. Between the two positions of a final project and the question of what are the results of my practice up to now, is the opportunity to explore more daring methods of execution that lean toward more rambunctious and expanded ideas. After the first lockdown in the summer of 2020 I went to see the Steve McQueen exhibition at the Tate modern. The way the show was curated really intrigued me. In amongst the mix of black box film suites and projectors suspended from the ceiling and aimed at the wall, there were screens that were suspended from the ceiling also. One screen in particular hosted the film “Static”, containing shaky camera work as a helicopter circles the Statue of Liberty. What I found most interesting is how the screens suspension carved up the space yet did not close it off. The ability to move around the film as it was playing, as well as being able to sit and view it from a bench against the wall, gave one the feeling that the film had a sculptural quality. In conjunction with the element of structure was the the choice of film and the movement within the film caused one to embody the sensation of being the helicopter and the projector at the same time.

Right. “Once Upon a Time” (2002), and “Static” (2009) are among the works that share an open space.

Credit...Richard Ivey

Fig. 2, “Once Upon a Time” (2002), left, and “Static” (2009), right.

Credit. Richard Ivey

So, how do fig. 1 and 2 link. How did I progress an idea from 2020 into the thought of a garbage truck in a wall? Part of my practice is about the study of time. Documenting thoughts, ideas and processes in real time. Sometime to yield from the consciousness a materiality that can manifest in making, materials and process. Whilst making my own film that embodies the study of time and place and progress, I had noticed that the program I was using to make the film (iMovie) sometimes arbitrarily fixed the ratio of the film. The result was that the film, as it played, would alternate between a 1:1 ratio and a 16:9 The former causing large black blocks that would sit either side of the image (see fig. 3 and 3a.)

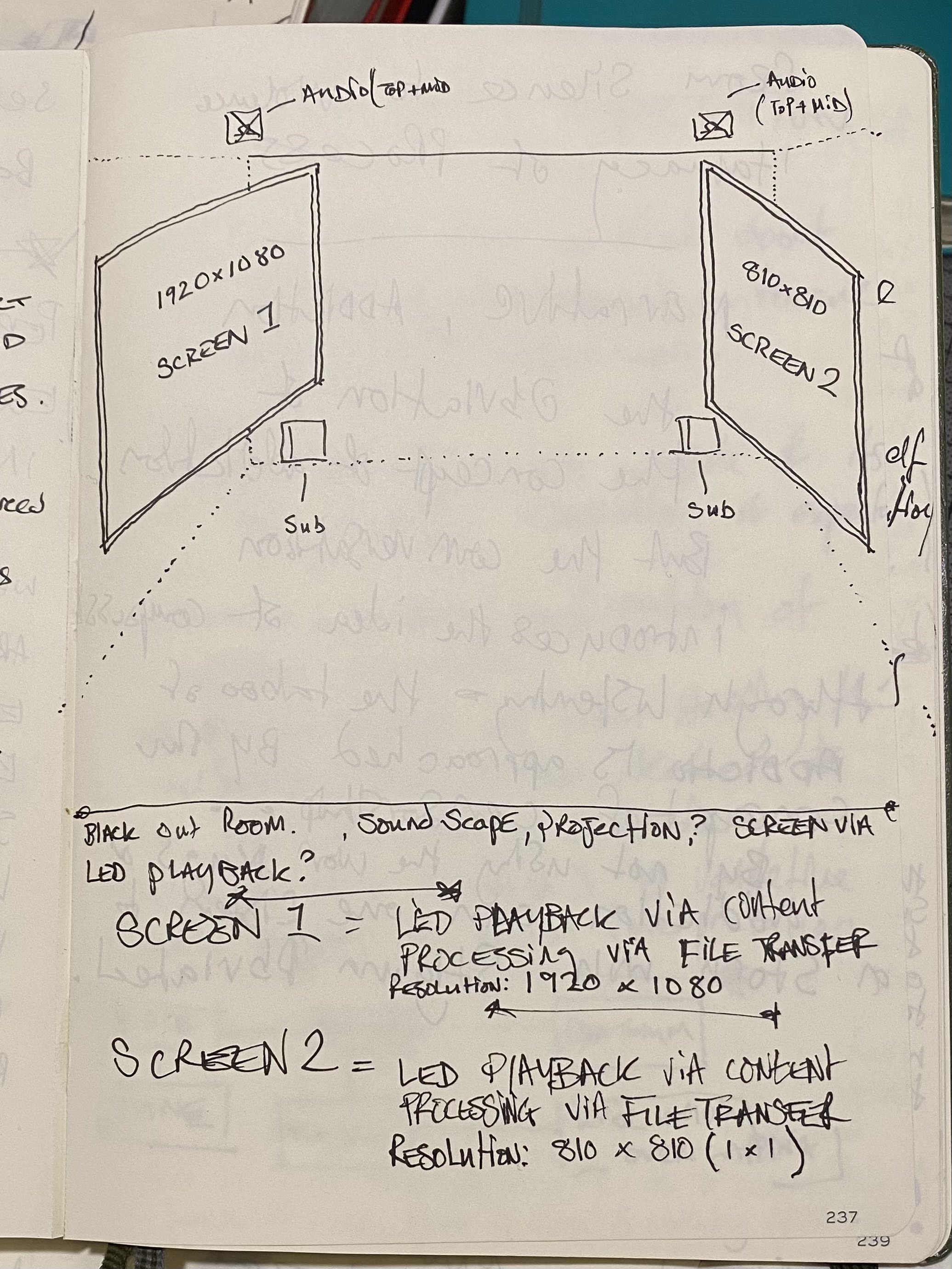

This visual aspect of the formatting and size created, in my forethinking, an opportunity to explore the surface area required to give residency to each image. If the film plays on just one surface, what happens to the large black margins? how does a square image inhabit a rectangle screen? Are we treated to any residue of the deserted space that the lack of image leaves behind? For me these are really important questions, not only as a demonstrative exposé of how my thinking, in relation to meaning and context, has evolved but more so, that these considerations are key for the work to succeed. Nam June Paik, an artist who like McQueen has a very large presence in my method and influences my approach to thinking, once wrote – and here I liken the mention of ‘fixing’ to how the apparatus of the screen frames an image: that “a television image could not be controlled or fixed by the artist in any traditional sense. It was therefore ‘in-deterministically determined.” [1] The fixing of image, posit the notion to consider what gets left out on a moment of change. Therefore, I found myself these last few weeks wondering -almost a year later - how to the fix the screen and surface, reception and screening. Like almost every idea, I started to jot down my thinking as projections. (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4, Stuart Lee (2021) Working nots on a screen idea.

From working notes and scribbles, I tried to visualise how my film could flip between two screens. Same one film, I saw it like viewers watching as the image jumps from one screen to the other and back again.

So, its a couple of months into the final year now, and as well as ceramics, i’m trying to innovate with my practice and veer into disciplines that I may not otherwise have tried. What doesn’t work for me is sitting on an idea too long. One of the biggest drawbacks to my practice is the element of permission. Allowing the internal narratives to spin reasons why I shouldn’t try something, just because, for example, a specific material has already been used or that an artist has tackled and mastered a certain method of production. What fails most in my process is the not making. This ability to forge ahead with ‘doing’ has led me to setting up a space here in the basement, so I can try ideas, plans and proposals in model form. (Fig. 5,6 and 7)

In Fig. 6, I wanted to see what the film, Cityscape (2020), might look like, as mentioned above. Earlier in this first block of the L6 year I took down a note from a seminar that had mentioned the artist Christo and Jean Claude. Remembering this I’ve started to see what a model of my final project may look like, were I to actually try to produce it as an artefact. Researching Christo and Jean Claude, I am starting to find small parallels to my own work. Two small indicators would be “architecture and concealment.” [2] What my work gives in its materiality, it withholds in purpose. The work below on the left (fig. 8) is an example of a Christo and Jean Claude maquette for a work they proposed in 1966-7 called storefront. Why this is crucial, is the work serves as a grounding and also furthers established disciplines within site specificity and in comparison too, informs my own practice in the context of residency and place.

Even though my proposal isn’t dealing directly with an external site, the placement within a space has to be considered in how the work functions as art. The proposal for this work considers a white cube setting, although that may not be the final setting, were this work to be taken out into the real world. So far we have an idea formed in film turning into a setting to test further ideas and create different experiences. My initial plan to see what the function of a space would take on in relation to screens in a room, has become a method to test production effects in relation to a surrounding. utilizing this methodology allows me to test multiple ideas in small scale. One of the benefits too, is being able to produce differing ideas and without the costs of making them come to life in the real world. This creates and opportunity contrast tangible thought process and allows a real world ‘feel’ to come into the space of thinking.

Having differing proposal ideas too, produces a situation where I have to consider which work might best be achievable. I say this as both final year proposals have gone way beyond some of the capacities of the spaces I am considering. Not only with their scale, but also with the choice of elements that make up the work outside of normal world parameters. Inside the maquette (Fig. 10) for example we are asked to confront live electricity. (see below. Fig. 11-12)

The three upright copper rods seen in fig. 11 (above) are designed to be electrified. The model allows the intricate particulars of the installation to come to light and at least if nothing else be imagined in a way that draws in the space so as to highlight any further localized complications.

Lygia Clark was a truly remarkable persona in the art world. She was never afraid to express her thoughts and to communicate with viewers on a higher level. [3]

Lygia Clark - Maquete para Interior No. 1, 1955

14 November 1968

Dear Hélio

[...]

As far as the idea of participation is concerned, as always there are weak artists who cannot really express themselves through thought, so instead they illustrate the issue. For me this issue does indeed exist and is very important. As you say, it is exactly the ‘relation in itself’ that makes it alive and important. For example, this has been the issue in my work since the sixties; if we go back even further to 1955, I produced the maquette for the house: ‘build your own living space’. [4]

The Brazilian artist Lygia Clark expresses the critical nature of relation by highlighting the importance of communication and the consideration of an audience. What is evident in my research into Lygia Clark is the use of structure and architecture in our work. Like Clark, I started as a painter, yet have tried to innovate in other mediums. One of these mediums is concrete, and again like Clark, who was a lead proponent in the neo- concrete movement in Brazil, this use of aggregate continues my own exploration into the three dimensional communication form of sculpture and concrete.

Lygia Clark, Construa Você Mesmo Seu Espaço para Viver (1964).

I see this process as a continuation in the development of my practice, informed by the work of Bruce Nauman, Rachel Whiteread, Doris Salcedo and Cornelia Parker. Therefore, one can consider the space as well as the sculpture itself? What if the space, building, or environment becomes part of the work itself? This thinking has instructed how I approached another idea that I wanted to produce for a possible Major Project Proposal. Rather than trying to think or explain the work, what if the work was brought about by a maquette? Again, inspired through my research I forged ahead to make a proposal for a work titled (working title) ‘Garbage Truck in a Wall’. The Work is part installation part performance. The work can only amplify its prominence and signification by inserting itself within the structure of the building. What is extremely significant and should be highlighted is the journey across the time between how a film about a helicopter hanging in the Tate, turns into a refuse truck in a wall. I am toying with the idea to propose this as my final project. The research has led to meetings with the London Met administrative body. The university’s position is that if the proposal (inserting a garbage truck in a wall (fig. 1.) goes ahead, there are lots of structural considerations, points of accountability, scope of works, and risk management to be taken into account. Meeting Marcus Bowerman head of MakeWorks and Jen Ng who is an architect and works for the university’s Schools Project Office we discussed the physical and practical challenges. Just a few of these considerations and implications included road closures, elements of project ownership and post exhibition remedial work. I’m not sure how easy it would have been to visualise this whole process. The development of an idea takes on a differing form when realised as a thing. The model form produces different transferences that are able to be grasped in a way that the drawn form cannot manifest. I see the making of these maquettes as thinking in real time style of research. A key aspect of this method is how I can consider space, spatiality and wether I want my work to exist in large scale.

[1] Nam June Paik, Video Time – Video Space, ed. by, Toni Stooss and Thomas Kellein, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993, p. 31

[2] ‘Christo and Jeanne-Claude in the Vogel Collection’, National Gallery of Art, <https://www.nga.gov/features/slideshows/christo-and-jeanne-claude-in-the-vogel-collection.html#slide_3> [accessed 20/11/2021] (Slide 3)

[3] Nadia Herzog, ‘Pioneering Work by Lygia Clark that Pushed the Limits of Sculpture on View at Alison Jacques Gallery’, Widewalls, (May 2016) <https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/lygia-clark-exhibition-alison-jacques-gallery-london> [accessed 23/11/2021]

[4] Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art, ed. by Claire Bishop, (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2006), p. 113.